Dear Mr. Hanks,

I am writing to you not as a fan of your remarkable work, but in desperate need of your help. As you’ll see, this concerns your portrayal of Viktor in “The Terminal”, which has shocking relevance to a close friend of mine in the present moment.

There is a real-life Viktor currently stranded in Istanbul Airport. My dear friend, Adnan Alfaki, is a Sudanese IT engineer who has been trapped there since May 18, 2024. Despite holding valid travel documents, he was wrongfully offloaded from his flight to Cuba by Turkish Airlines and Airport Security. Adnan’s situation is dire. He has no access to food or legal assistance, and his physical and mental health are deteriorating rapidly. Unlike Viktor, Adnan doesn’t have a friendly airport food service worker to help him; he has been surviving for weeks on vending machine snacks .

Adnan’s plight is compounded by the fact that he cannot return home to Sudan. Not only is the the airport in Khartoum closed as a consequence of the ongoing war, but Adnan escaped from Sudan while being hunted by the RSF intelligence service. He is caught in an agonizing limbo, much like your character but without the endearing support Viktor received. The parallel to “The Terminal” is uncanny, yet this is a grave reality with a man’s life hanging in the balance.

Full information on Adnan’s situation can be found below.

For weeks, we have tried every avenue we could think of to get Adnan out of the airport:

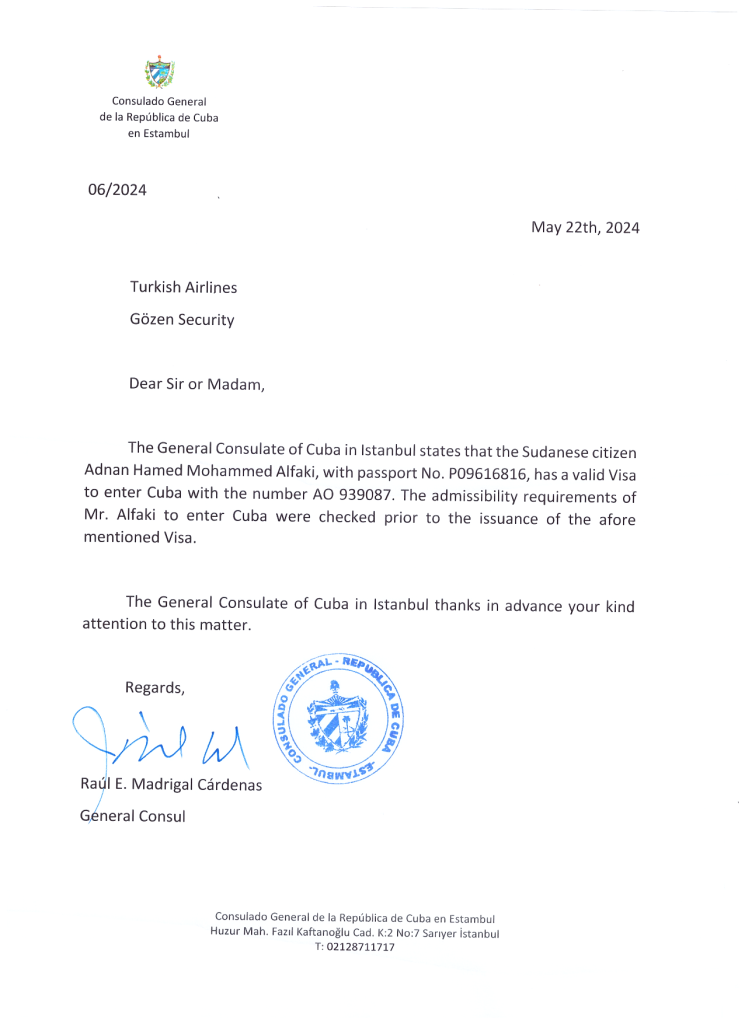

- We have obtained a letter from the Consul General of Cuba in Turkey, attesting to the validity of Adnan’s visa; but Turkish Airlines and airport security ignore it.

- I am ready to purchase Adnan a ticket on an Air France flight to Havana; but it changes planes in Paris, and France requires a transit visa of Sudanese passport holders (and very few others), which they will not issue.

- We have the Istanbul office of the UNHCR and its local law firm ready, willing, and able to help; but they have no legal access to Adnan until he crosses immigration into Turkey, which he cannot do without a Turkish visa.

- Turkish Airlines has instructed the Red Crescent Society not to take claims for refuge or assistance from its stranded passengers; and they refuse to speak with Adnan or accept his request for assistance.

- The medical clinic at Istanbul Airport has refused services to Adnan, even as he suffers the effects of malnutrition.

- Through contacts at The New York Times, we have brought the story to the attention of its Istanbul bureau chief; but it hasn’t yet interested him.

Your influence — even the merest public expression of compassion for Adnan’s situation — could make a difference in drawing attention to his predicament and helping us to finally persuade Turkish Airlines or a French Consulate to resolve this crisis. Everyone knows “The Terminal” and, thanks to the deep humanity of your performance, everyone identifies with Viktor. Even Adnan knows the film! In the first days, when we thought that surely this would be resolved, I joked with him that at least he might get a chance to date Catherine Zeta-Jones. He laughed and said, “I’ve been looking for her, but I don’t see her anywhere.”

Adnan’s story is not comedy of bureaucratic failure, but a profound tragedy, with a real life getting ground to dust because corporations and governments cannot be bothered to care. Please consider lending your support to ensure that Adnan can find his way out of this terminal torment and into the safety and dignity every person deserves.

Thank you for your time and consideration.

Warm regards,

Mark Jacobs

mbjesq@gmail.com

ADNAN ALFAKI: WRONGFULLY STRANDED IN ISTANBUL AIRPORT BY TURKISH AIRLINES

CONTENTS

- Executive Summary

- Statement of Facts: Wrongfully “Offboarded” from Flight and Stranded in Instanbul Airport

- Key Documents

- Narrative: Escape from Sudan

- News: Turkish Airlines’ Pattern of Callous Discrimination

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

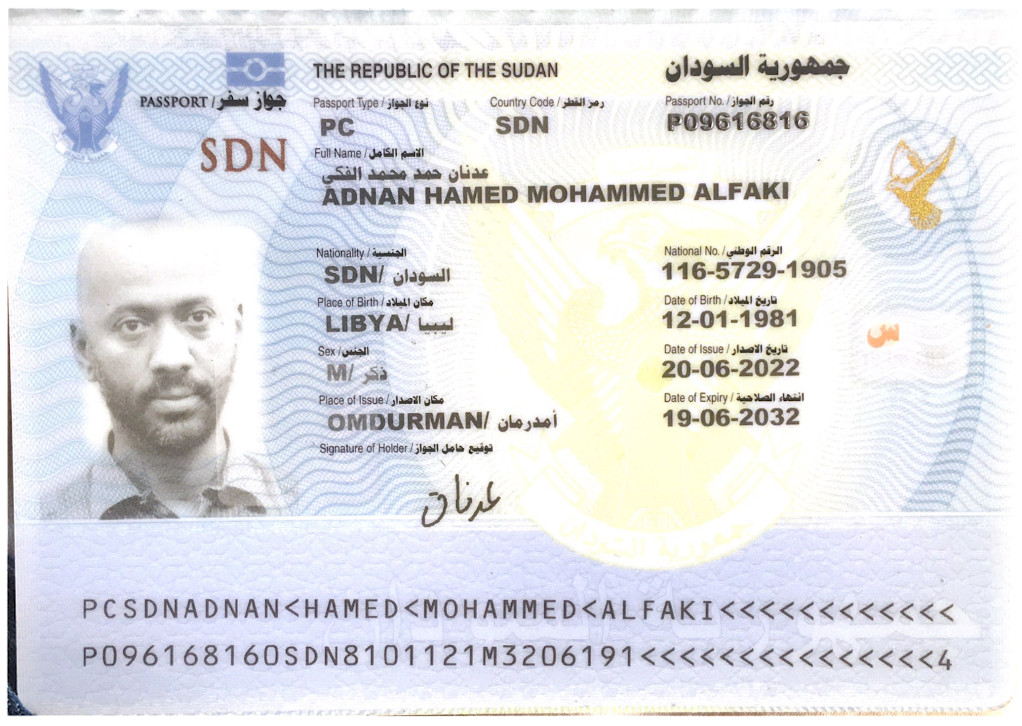

ADNAN HAMED MOHAMMED ALFAKI

Age: 43

Profession: Information Technology Engineer

Nationality: Sudanese

Turkish Airlines Ticket No.: 235 2226 2526 71/C

Turkish Airlines Online “Feedback” No.: TK-10862609

Sudan Passport No.: P09616816

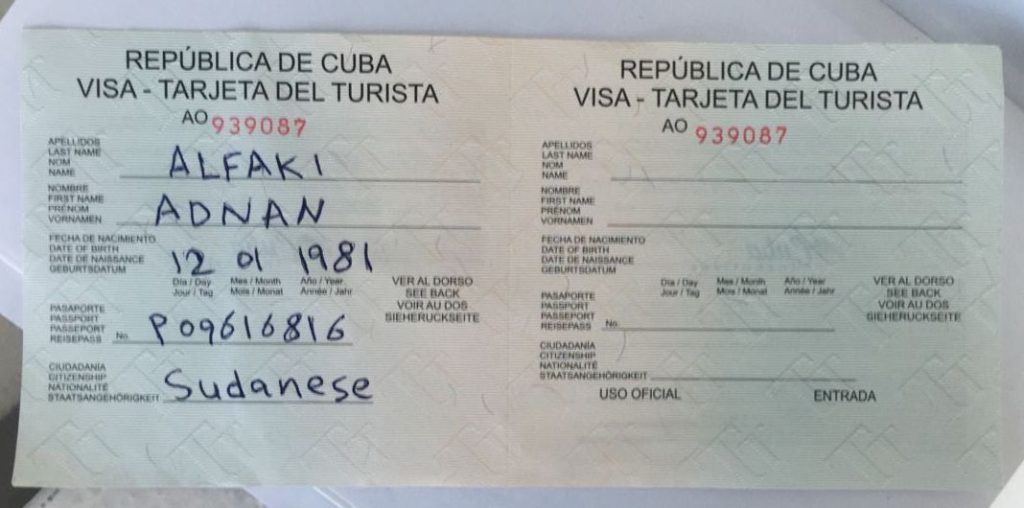

Cuba Visa No.: AO939087

Telephone: +249 99 950 4893

Email: adnanhamed2023@gmail.com

Summary of Current Status:

- Escaped from the war in Sudan to UAE in September 2023.

- Traveling from UAE to Cuba on a visa issued by the Cuban Consulate in Abu Dhabi.

- “Offloaded” from connecting flight in Istanbul by Gözen Security and Turkish Airlines, and detained since 18 May 2024 in Istanbul Airport. They said they “suspected” his visa was “forged”.

- The Consul General of Cuba in Turkiye has certified, in writing, that Mr. Alfaki’s travel documents are valid for travel to Cuba.

- Gözen Security and Turkish Airlines ignore the consular letter and refuse to speak with the Cuban Consulate to confirm the validity of Mr. Alfaki’s travel documents. Each says the situation is within the exclusive control of the other, and each is unwilling to further discuss the matter with either Mr. Alfaki or me – or even with each other.

- Mr. Alfaki has been removed to a section of the airport where it is impossible for him to obtain food, other than through the kindness of (non-Turkish Airlines) airport employees. He has gone hungry many days since 18 May and is presently quite malnourished and unwell.

- Since being stranded by Turkish Airlines in IST, Mr. Alfaki has met several other Africans who have been refused onward travel to their properly visa’d destinations by Turkish Airlines. One woman, a diabetic from Algeria, had her insulin confiscated and was forced by failing health to return to Algeria.

- Because Mr. Alfaki has no visa to enter Turkiye and leave the airport, he is unable to meet with lawyers or multilateral agencies who can assist him.

Contacts:

Adnan Alfaki: +249 99 950 4893, adnanhamed2023@gmail.com

Mark Jacobs: +1 604 617 8768, mbjesq@gmail.com

STATEMENT OF FACTS

Wrongly “Offboarded” from Flight and Stranded in Istanbul Airport

Adnan Alfaki departed Abu Dhabi on 17 May on Turkish Airlines flight No. TK867 for Istanbul. His itinerary called for a change of planes in Istanbul, to depart for Havana, Cuba on Turkish Airlines flight No. TK183 at 02:00 on 18 May. He carried with him a valid passport, issued by the Government of Sudan, and a valid visa for entry to Cuba, issued by the Cuban Consulate in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. When Mr. Alfaki checked-in and boarded on his originating flight from Abu Dhabi, his travel documents were fully inspected by Turkish Airlines staff and airport security, including his Turkish Airlines ticket, his passport, and his visa for Cuba. Because these were valid documents, he was checked-in for the flight, allowed to board, and flown to Istanbul without incident. (Mr. Alfaki’s travel documents are attached below.)

He arrived in Istanbul the night of 17 May and awaited his connection to Havana, early in the morning of 18 May.

As Mr. Alfaki was boarding his onward flight to Havana (TK183), he was prevented from traveling (“offloaded”) by Gözen Security, the security contractor hired by Turkish Airlines. I was told by Turkish Airlines gate agents that Gözen Security believed my travel documents were forged and Turkish Airlines would not allow me to fly to Cuba. They told him, “Go back to Sudan.” Mr. Alfaki pleaded with them, but they refused to assist him in any way, leaving him alone in the international terminal of the airport.

It was 02:00 AM on a Saturday morning. Mr. Alfaki had very limited internet connectivity at the airport, knew no one in Turkiye, and had no idea how to get help.

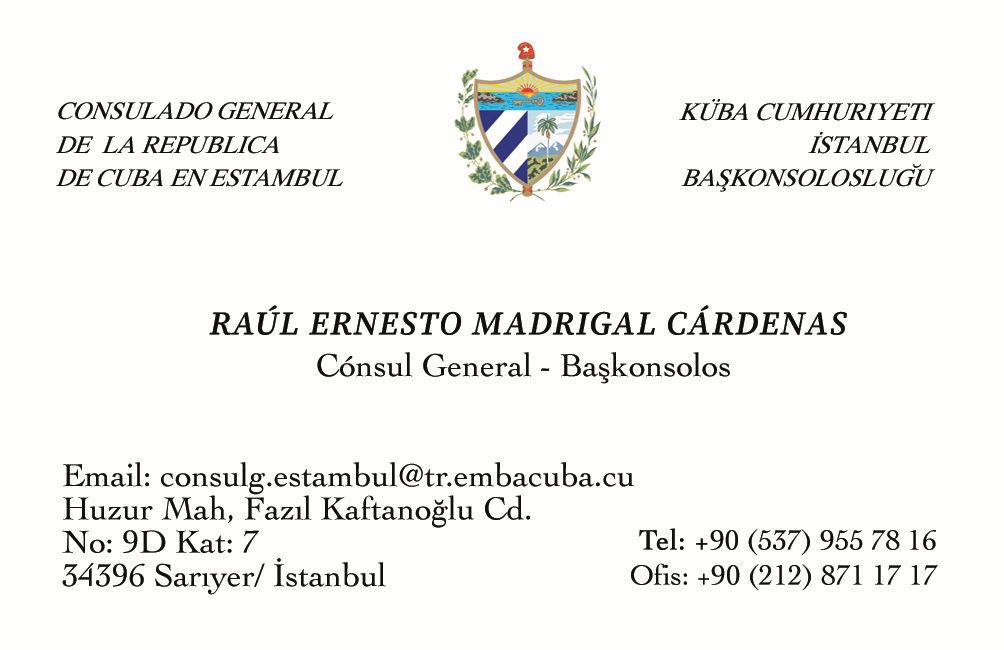

On 21 May, when I learned of Mr. Alfaki’s dilemma, I contacted the Cuban Embassy in Ankara. They, in turn, put me in contact with the Cuban Consulate in Istanbul. By 22 May, the Consul General of Cuba in Turkiye, Mr. Raúl Cárdenas, had written to both Gözen Security and Turkish Airlines, certifying that Mr. Alfaki’s travel documents were authentic, legal, and valid for entry to Cuba, and that he would be welcomed in Cuba when he arrived. (Mr. Cárdenas’s letter is attached below.) Mr. Cárdenas provided Turkish Airlines and Gözen Security with his personal telephone number in Istanbul and invited them to call if they had any questions. (Mr. Cárdenas’s business card is attached below.) Neither Gözen security nor Turkish Airlines ever called him.

Also on 21 May, I started writing and making telephone calls to both Gözen Security and Turkish Airlines. I was eventually advised by both Gözen Security and Turkish Airlines that the only way to make a formal complaint in the matter was fill-out an online “Feedback” form at the Turkish Airlines website. Gözen Security refused to discuss the matter further, stating that Turkish Airlines has sole responsibility in the matter:

Our company has been appointed to conduct a preliminary security check on behalf of the air carrier, taking into account international rules and regulations and sensitive implementations of the destination country, in order to ensure that passengers are not deported from the destination country and that both the passenger and the air carrier are not imposed a monetary penalty. It is our contractual obligation to inform the air carrier about whether the passenger meets the above-mentioned requirements and about possible risks before the flight, if any. The final decision regarding the acceptance of the passenger to the air carriage belongs entirely to the air carrier and not to our company.

Between 18 – 23 May, Mr. Alfaki tried repeatedly to find a Turkish Airlines employee at the airport to consider his situation, read the letter from the Cuban Consulate authenticating his travel documents, and put him on a flight to Havana. On 23 May, Turkish Airlines removed Mr. Alfaki to a place within the international terminal’s connecting-flights area where there are no restaurants, no kiosks, and it is extremely difficult to obtain anything to eat. They told him, “Soon you will want to go back to Sudan.” Mr. Alfaki obtains food only through the kindness of (non-Turkish Airlines) airport employees.

On 26 May, Mr. Alfaki received the following form-letter response from Turkish Airlines to his online “Feedback” request, TK-10862609, which makes clear that Turkish Airlines did not make a good-faith investigation of his situation:

Dear Andan ALFAKI,

Based upon your feedback we have made a very detailed investigation about what happened during the boarding time for TK0183 Istanbul to Cuba flight on 18th of May 2024.

Certain countries, such as the US, UK, and Israel, have very strict rules concerning visa and passport procedures. The visa and passport controls of our passengers who are traveling to these countries are carried out by the company Gözen Security.

Our passengers' check-in operations are done following the approval of Gözen Security.

In reference to this information, we wish for you to know our regret at the unfortunate situation that has occurred.

Sincerely yours,

Fatime M.

Customer Representative

TURKISH AIRLINES INC.

Customer Contact Center

We are at an impasse. Gözen Security says Turkish Airlines makes all decisions regarding whether a passenger may fly. Turkish Airlines says Gözen Security alone decides. Neither company has properly considered the letter from the Cuban government, saying that Mr. Alfaki’s travel documents are authentic and valid, and that he is welcomed in Cuba. Neither company will consult with the other to resolve the problem. Neither company will speak with Mr. Alfaki.

Mr. Alfaki is exhausted, hungry, and demoralized. He purchased a ticket from Turkish Airlines for travel to Havana, Cuba. He held proper, valid travel documents, which were fully inspected before his departure in Abu Dhabi by Turkish Airlines and which have since been authenticated by the Cuban government. Turkish Airlines can easily solve this problem.

And Turkish Airlines must solve this problem. Turkish Airlines is subject to European Union regulation EC261 with respect to flights departing Istanbul, as well as to the Warsaw and Montreal conventions on passenger rights.

Mr. Alfaki has suffered enough. It is inhumane for Turkish Airlines to delay another day. The next flight from Istanbul to Havana departs at 02:00 AM tomorrow morning. Mr. Alfaki should be on it.

Thank you for your prompt and compassionate attention to this matter.

Mark B. Jacobs

mbjesq@gmail.com | +1 604 617 8768 (Canada)

DOCUMENTS

ESCAPE FROM SUDAN

29 May 2024

My name is Adnan Hamad Mohamed Alfaki. I am 43 years old, Sudanese, and I lived in Omdurman, Sudan, before I fled the country in 2023.

I cannot return to Sudan.

This story begins when I joined the Sudanese Ministry of Defense (MOD) in a junior information technology position in 2018. My education and training is in telecom and IT engineering. At the MOD, I was a trainee in the networking department, where my job was to maintain network devices and surveillance devices, including DVR and NVR systems. Part of my job was also to ensure that surveillance cameras inside the building and around the northern perimeter facing the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) tower were functioning.

It is important to understand that, from the time the Janjaweed militia was made a formal part of the military structure and brought within the MOD in 2013, neither MOD, nor the Armed Forces of Sudan (AFS) ever fully trusted the RSF. And the RSF certainly never trusted AFS or MOD, which led to the current war.

I was part of a team responsible for installing street surveillance cameras that covered a significant portion of the three capital cities. In July 2018, a small team of us were asked to install external cameras at the former security building, later known as the RSF Communications Building. We completed the work under constant supervision of RSF soldiers.

An RSF intelligence officer named Issam Eldin Khalid approached us while we were taking a break from our work. He invited us for breakfast, praised our work, and generally engaged us in polite conversation, asking us about ourselves. I thought little of this, thanked him, and went back to work

Two days later, I received a call from an unknown number. The caller identified himself as Issam Eldin Khalid, the RSF intelligence officer who had taken my colleagues and me to breakfast. He asked me to meet him. When we met, he asked me to work for the RSF. I declined, citing my commitments to study and work at the MOD data center. What I did not disclose was that I would never willingly work for the RSF. They are the murderous militia who carried out the terrible genocide in Darfur on behalf of the al-Bashir regime, as well as other atrocities in South Kordofan and Blue Nile states.

From time to time, without notice, Issam Eldin Khalid would suddenly show up and approach me. He would ask if I had changed my mind about the job offer, promising substantial financial incentives and transportation benefits. I always declined. Sometime in early 2019, perhaps in February, he told me that working for RSF would not require me to quit my job at MOD. This was a frightening conversation. For the first time, I understood that RSF intelligence was not simply interested in my IT surveillance skills. They wanted me to spy from within MOD. I declined, but he was very angry. I was terrified, but did not know what to do.

Over the next months, when I was out on the streets in Khartoum or Omdurman, RSF soldiers would suddenly show up and tell me they needed me for a job. They would push me into a car and blindfold me and take me to various locations around Khartoum and in the Tayba Al-Hassanab camp, as well as in the homes of RSF officers. The work itself did not seem important to the RSF. Any video or IT technician could have performed the tasks. The important thing was for them to demonstrate that they could control me. I was never paid for any of this work and each time I was abducted, I feared for my life. This continued until April 2019, at the start of the sit-in at the General Command. As a pro-democracy advocate, I immediately quit my work at MOD General Command. But, when coming to that decision, it occurred to me that by leaving my job at MOD, I would no longer be useful to RSF intelligence and that they would leave me in peace.

I found work maintaining laptops and phones and installing surveillance cameras for small establishments and homes. My life was peaceful for a while. Sometime in 2020, I was at a tea vendor’s stall near Al-Shuhada market in Omdurman, when Issam Eldin Khalid suddenly appeared and sat down. I asked how he knew where I was. He laughed and said, “Did you forget I am an intelligence officer? I can find out everything about you.” He told me they had a camera installation job and that a driver would pick me up from Al-Shuhada at 9 AM the next day. I told him I was busy and it was impossible for me. He said, “What choice do you have?” Without another word, he left the tea stall.

The next morning, a fully tinted Hiace van arrived with two RSF members in uniform. They blindfolded me and took me to an undisclosed location where I installed the cameras. At the end of the job, Issam Eldin Khalid arrived at the site and accompanied me in the van back to Al-Shuhada market. He asked many questions about street camera installations I had done for MOD, as well as questions about other aspects of MOD surveillance capabilities. I told him I was only a trainee while at MOD General Command and had been gone too long to remember any of the details that would be useful to him. He questioned me about extremely technical details, including IP addresses, server information, and passwords. Although he never used violence during this interrogation, he made it clear that my life depended on me telling him everything I knew. I pleaded that I would tell him if I knew anything, but that most of what he was asking about were details managed by security officers with special network access credentials and, to the extent I might have once known things like IP addresses, these were not details that anyone could possibly remember after time had passed. I was terrified after the van left me at Al-Shuhada, but over the next few months I began to relax when the RSF seemed to have stopped pursuing me.

This changed suddenly one day in April 2023, when the war started. I received a call from an unknown number and it was Issam Eldin Khalid. I was scared and hung-up the call.

The next day my friend Ahmed Mohamed and others were moving goods from the shop where I worked, trying to safeguard things from looting and destruction. Uniformed soldiers of the RSF came asking for me. They were angry and violent but left the shop. Ahmed Mohamed called me immediately. I sent my family (parents, brothers and sisters) away from the family home for their safety. I then traveled with a neighbor to his village in Um Kate, north of Khartoum, and from there to Shendi, Atbara, Kassala, Gedaref, and eventually Damazin. It wasn’t safe to travel via Medani, so I tried to gather money to travel to Ethiopia. Traveling through Ethiopia was extremely dangerous for me, but I had no choice. My family was originally from the Benishangul region, which was taken by Ethiopia from Sudan. My father was the former Health Minister of the region, and spent two years in an Ethiopian jail. My family and I were removed from our home at gunpoint by Ethiopian soldiers and expelled from the region.

I contacted a friend in the UAE for a visa. After receiving it, I traveled from Medani to Gedaref, then to Ethiopia through the Gallabat crossing, and finally to Dubai, settling in Abu Dhabi in October 2023, when I was granted a one-year, non-renewable emergency visa.

The relationship between UAE and the RSF is well known. UAE provides money, weapons, logistical support and intelligence to the RSF, as well as hiring mercenaries from Chad to fight with the RSF. In April 2024, there started to be alarm among the Sudanese I knew in Abu Dhabi that RSF officers were present in UAE. I was warned by a friend that the RSF could reach me even abroad. Fearing for my safety, and with my legal stay in UAE soon to be terminated, I applied for a tourist visa for Cuba and left Abu Dhabi. My journey to Cuba was stopped in Istanbul, by Turkish Airlines and Gozen Security, where I remain stranded at the airport.

TURKISH AIRLINES: A PATTERN OF CALLOUS DISCRIMINATION